Local Life - A Guide To Living And Working In Albany NY

Whether you're currently working or living in Albany NY or looking to move to the area, you probably already know what makes this such a great place - a thriving locale that includes something for everyone! The Capital Region provides residents access to world-class education, recreation, urban sophistication, cultural attractions, and career opportunities.

Find properties for sale, apartments for rent, local realtors, and other resources in our Real Estate Guide.

Albany is home to a diverse array of unique neighborhoods! Learn more about each one.

On a tight budget? Check out our list of coupons you can use at Albany area businesses!

From Saratoga and Lake George to Vermont and the ADKs, discover fun daytrips from Albany.

You'll find a vast assortment of restaurants and an exciting nightlife scene in the Capital Region.

Visit our Capital Region events calendar and stay current on upcoming events.

Find home improvement pros and landscapers that can help you with any home-related project.

Find the health services you need, from insurance providers to urgent care facilities.

Learn more about the Albany County Legislature, Albany City Officials, and Sheriff's Department.

Post a job or browse Capital Region job listings and other employment-related resources.

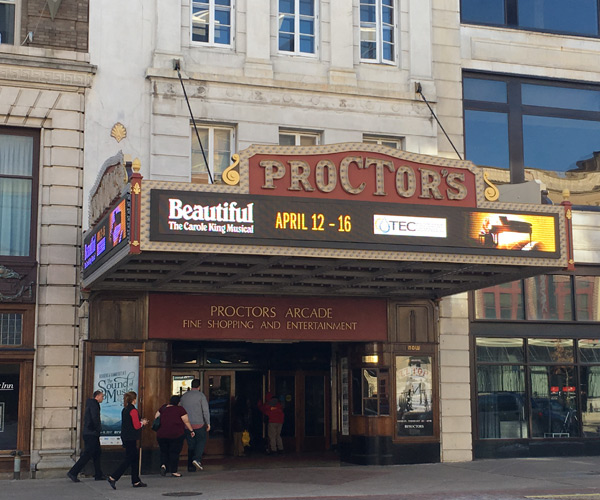

From the arts and historic sites to kid-friendly attractions and shopping, there's lots to do here.

Find services to help the senior citizens in your life, from housing to financial advisors.

There are hundreds of businesses and services to take advantage of in the Capital Region.

You'll never be bored in Albany: there's so much to do! Check out this quick list of fun things in the area.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Did we miss one? Did one of these places close? Send us a note!